WorldStrides Updates

Power in Numbers: Organizations and Leaders of the Civil Rights Movement

When you think of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, you likely picture Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other iconic figures. These powerful individuals, however, weren’t always the ones spurring the masses into action. On the contrary, many grassroots organizations and behind-the-scenes leaders mobilized throughout the South, eventually thrusting these now-historic figures into the spotlight. We’re taking a closer look at some of the unsung heroes and community organizations who fought for progress and racial equality.

As the faces of integration and tragic victims of racial violence, youth were a driving force in the Civil Rights Movement. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education struck down racial segregation in public schools, but integrating school systems was a drawn-out battle with young people on the front lines. Three years after the landmark case, the Little Rock Nine tested the ruling, walking past angry mobs into Central High under the protection of federal troops. Flanked by federal marshals, six-year-old Ruby Bridges was the first student to integrate her New Orleans school in 1960, after repeated delays from White parents and legislators. Flanked by federal marshals, Norman Rockwell immortalized her courageous walk to school in the painting “The Problem We All Live With.”

White anger often turned violent, even against children. Emmett Till had been visiting relatives down South when he was accused of harassing a white woman. Two men kidnapped, beat, shot, and killed him. Images of his mangled body “shocked the nation” and helped ignite the Civil Rights Movement. Lynchings remained “public acts of racial terrorism” into the 1950s.

In Birmingham, AL, youth witnessed their parents organizing and marching, and the Children’s Crusade was formed in the spring of 1963. Trained in non-violent tactics, thousands of young people took to the streets near Kelly Ingram Park in peaceful protest. They were met with the brutal force of water hoses, batons, and attack dogs. That September, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley were killed when a bomb detonated outside 16th Street Baptist Church across from the park. The contempt, hate, and brutality lodged against innocent children elevated racial inequality into the national dialogue, brought forth White allies, and inspired more citizens to stand up for change.

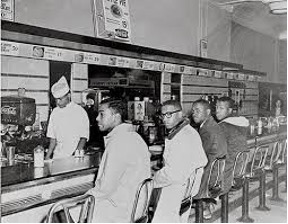

On February 1, 1960, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, and Jibreel Khazan, undergraduate students at North Carolina A&T State University, walked into the Woolworth’s store in downtown Greensboro, NC, and engaged in a peaceful sit-in protest. During Jim Crow, African-Americans and people of color weren’t allowed to sit and be served at lunch counters or in restaurants nor access public amenities, such as libraries, recreation centers, and movie theaters. These forms of racial segregation were discriminatory and unjust but were legally enforced.

Several months after the Greensboro sit-in, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization that “advocated confrontation of segregation through civil dissent,” convened a conference of student activists, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was born. The SCLC had grown out of the Montgomery Improvement Association, which helped organize the bus boycott in 1955-1956. The aim was to amplify and coordinate those efforts across the south, and part of their success was in the recruitment and training of university students and other activists. SNCC, in turn, was instrumental in launching the Freedom Rides of 1961. Testing yet another Supreme Court decision, more than 400 Black and White passengers—mostly young adults—rode together on interstate busses through the Deep South. Some of the busses were firebombed, the Ku Klux Klan used brutal intimidation tactics, and local and state officials condemned the riders, but the young activists continued to practice non-violent methods to promote social change.

One of those Freedom Riders was John Lewis, later a U.S. Congressman from Georgia until his death in 2020. As a young seminary student in Nashville, TN, he had been “mentored…in the philosophy and tactics of nonviolent direct action.” Whether sitting, riding, or marching, Lewis and his peers were instrumental to the Civil Rights Movement. They built a legacy of youth development and leadership that lives on today through the work of community organizations.

The power of the people to effect change arguably was most evident in the fight for voting rights throughout the South. The 15th amendment, passed in 1870 during Reconstruction, gave all men the right to vote, “regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” But as African Americans gained more political power, many states enforced conditions, such as literacy tests, to limit their voting rights. The discrimination and abuse were most pronounced in the South, especially in Alabama.

Years of voting rights campaigns organized by the SCLC, SNCC, and local leaders were met with violence. On March 7, 1965, hundreds of peaceful protestors led by Rep. Lewis began their march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma to Montgomery, AL. State troopers, county police, and private citizens confronted them, inflicting injuries with batons, tear gas, and whips. The violence boiled over onto television screens and newspaper covers; Bloody Sunday “jolted the conscience of a nation.” President Lyndon B. Johnson used the momentum to push for the passage of the Voting Rights Act, eventually signed into law that August.

After a second march to Montgomery, was deemed too unsafe to progress, a third attempt was launched on March 21, 1965. Four days later, 25,000 marchers successfully arrived at the Alabama State Capitol Building, demanding their rights be upheld. By the following year, thousands of Black citizens were registered to vote in Selma and a handful were running for office. The 54-mile route the marchers followed is now a National Historic Landmark.

The U.S. Civil Rights Movement recognized leadership throughout the community. In 1962, Fannie Lou Hamer used the power of her singing voice to calm her fellow bus passengers after an unsuccessful attempt to register the group to vote. The SNCC saw her ability to command a crowd, and she soon became a community organizer. As one of the founders of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), she delivered stirring testimony before the 1964 Democratic National Convention to fight segregation in politics. She used her voice to ask a nationwide audience, “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

The work didn’t end in 1964. Countless other leaders and organizers impacted the Civil Rights Movement throughout the coming decades–and they still do today. No matter your background or the grade level of your students, a plethora of educational resources are available to provide more information about these driving forces behind the Civil Rights Movement.

Facing History and Ourselves is adding resources all month long on the themes of Black Agency & Black Joy and offers a variety of teaching ideas to connect to current events. The New York Times Learning Network has resources on race, racism, and racial justice. PBS LearningMedia has videos, interactive lessons, and media galleries that focus on Civil Rights movements. More resources on the Civil Rights Movement can be found here as well. As we celebrate Black History Month, we keep working toward a comprehensive understanding of our past so we can continue building a future grounded in justice and equality.

Writer Bios

Malaika Marable Serrano (she/her/hers) is a former faculty director that taught several service-learning programs in the Dominican Republic, Colombia, and U.S. She finds joy in volunteering with women’s leadership groups and has received multiple awards including a Fulbright fellowship and Excellence in Diversity and Inclusion from the University of Maryland.

Mariaelena Morales has joined many student trips to see hands-on learning in action, including a Civil Rights Trail tour through Alabama and Georgia. Mariaelena uses her history degree to develop content that helps teachers place our past in context and inspire students think critically about the issues.

Randi Chapman is on the Curriculum and Academics team for WorldStrides. She holds an MT in Secondary English Education and BS in journalism, with an emphasis on public relations. In addition to her entrepreneurial experience launching an independent business, Randi brings eight years of high school classroom teaching expertise. She works tirelessly to increase the accessibility of meaningful professional development and educational opportunities to educators and students around the world.

Related Articles

The 2024 WorldStrides Student Photo & Video Contest Gallery

When you think of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, you likely picture Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other iconic figures. These powerful individual...

Girl Scouts: Costa Rica Tour

When you think of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, you likely picture Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other iconic figures. These powerful individual...

2024 Mérida Pride Parade

When you think of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, you likely picture Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other iconic figures. These powerful individual...

Rise Up, Take Action: How to Support the LGBTQIA+ Community

When you think of the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, you likely picture Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other iconic figures. These powerful individual...